By Sharmarke Farah,

How the International Court of Justice (ICJ) will arrive its judgement on Somalia v Kenya maritime boundary delimitations?

The International Court of Justice (ICJ) has announced last month that it will hand down its final judgement on Somalia v Kenya Maritime Boundary Delimitation in the Indian Ocean. This case has been ongoing since August 2014, when Somalia lodged an application at the ICJ to initiate proceedings against Kenya pursuant to Article 36 (1) and (2), Article 40 of the statute and Article 38 of the rules.

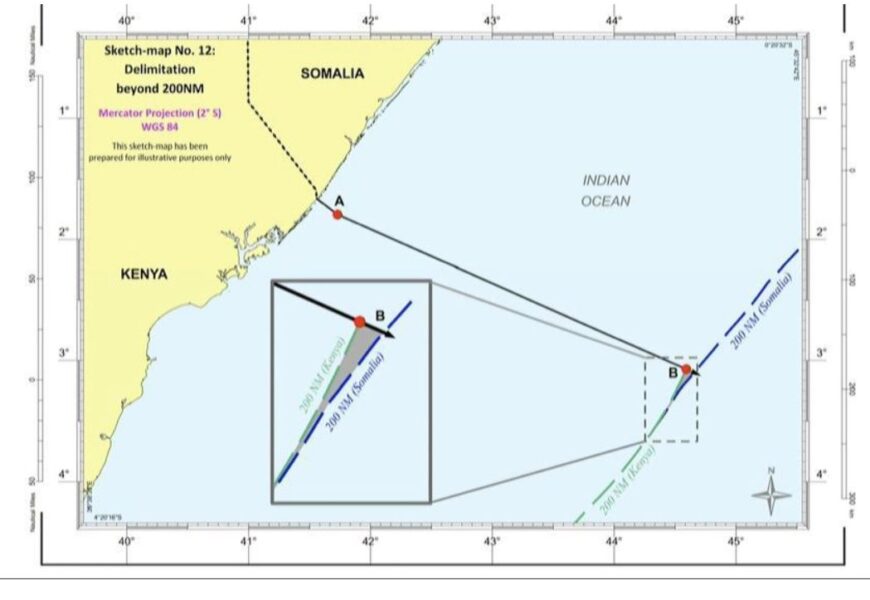

In this application, Somalia seeks the establishment of single maritime boundary between Somalia and Kenya in the Indian Ocean delimiting the territorial sea, exclusive economic zone (EEZ) and continental shelf, including the outer limits of the continental shelf, which is beyond the 200 nautical miles prescribed by the 1982 United Nations Convention of the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) for which both parties are signatories to.

Given this, Somalia seeks the maritime boundary delimitations be determined by the UNCLOS articles 15, 74 and 83. Article 15 deals with delimitation of the territorial sea whereas articles 74 and 83 govern delimitations of exclusive economic zone (EEZ) and continental shelf between states with opposite and adjacent coasts respectively.

However, Kenya contends that the maritime boundary between the parties should be a straight-line stemming from the land boundary terminus and extending east through the full extent of the territorial sea, EEZ and continental shelf. Kenya’s contention is not only in direct conflict to established norms and international customary laws, it is also inconsistent with Kenya’s 1972 Territorial Waters Act, which was grounded on the equidistance principle. Kenya has changed this law recently with the implicit intention to encroach and excise Somalia’s territorial waters, which is believed to be rich in oil and gas and other marine resources.

While we cannot speculate the reasoning that will underpin the court’s pending judgement, which is set to be announced on 12th October 2021, we can however draw on recent decisions by ICJ and ITLOS (International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea) pertaining to maritime boundary delimitations to make sense of it. Since the 2009 Black Sea judgement (Romania v Ukraine), the ICJ and ITLOS have departed from using the two-stage approach (equidistance principle and relevant circumstance) to a three-stage approach (equidistance principle, relevant circumstance and disproportional test) in delimiting maritime boundaries.

Under the three-stage approach, the court first sets up provisional equidistant line as a starting point, then it considers if there are relevant circumstances, which would make necessary to adjust or shift the equidistant line and finally it applies the disproportional test so as to arrive an equitable to solution between parties.

For instance, the 2012 Bangladesh v Myanmar maritime boundary judgement, the Tribunal followed through the three-stage approach to arrive its final decision on the maritime delimitation. Pursuant to article 15 of the UNCLOS, the Tribunal has first set up provisional equidistant line from the base points, then it has considered as to whether St Martin Island is a relevant circumstance, which require adjusting or shifting the equidistant line so that Bangladesh to exercise its right to a 12 nautical mile territorial sea around the island, in particular, where it does not overlap with Myanmar’s territorial sea and finally the Tribunal had decided to draw a single line for both the EEZ and the continental shelf.

Likewise, Romania v Ukraine, the Court first established provisional equidistant line and then went on to consider relevant circumstance, considering a number of factors, which included, among other things, the enclosed nature of the Black Sea and the presence of Serpent Island in the area of the delimitation. Following this, the court concluded that these factors have no bearing on the provisional equidistant line and found that there is no need for adjustment.

In conclusion, considering the above discussion, with respect to Somalia v Kenya maritime boundary despute, it is more likely than not that the ICJ will ground its judgement through the three-stage approach in delimiting the Indian Ocean maritime boundary between the two neighbouring countries. In accordance with articles 15, 74 and 84, the court will first set up provisional equidistant line between the two countries extending through the full extent of the territorial sea, EEZ and continental shelf ‘at the nearest points on the baseline from which the breadth of the territorial seas of each country is measured.’

Second, the court will take into consideration if there are relevant circumstances, which is absent in the case of Somalia and Kenya, given that there are no islands or geographical features in either side, which would make necessary to adjust or shift the equidistant line. And finally, the court will apply the disproportionate test, which is used to ameliorate the adverse impact that would stem from the existence of concave and convex coastlines, which would likely produce a cut off effect if strict equidistance principle is applied.

Given this, it appears that neither Somalia nor Kenya will suffer should the Court applies strict equidistance principle. However, it remains to be seen how the ICJ arrives its judgement on Somalia v Kenya Indian Ocean maritime boundary delimitation.